Before 1778

Between initial settlement of Kauaʻi around 1200 A.D. and the arrival of Captain Cook, Waimea developed into a major population center on the West Side of Kauaʻi. Aqueducts from the Waimea River channeled water and nutrients from the enormous catchment of Waimea Canyon to an extensive system of loʻi (wetland agricultural terraces) that provided a reliable source of taro. Areas with such abundant agricultural production often developed into major chiefly centers (like Wailua, Kauaʻi, and Waipiʻo Valley on Hawaiʻi Island).

January 20, 1778

Captain Cook’s ships Resolution and Discovery anchor in Waimea Bay. Ship’s surgeon William Ellis draws a watercolor of the Waimea coastline from the sea entitled, “View of Atowa, One of the Sandwich Islands,” which depicts thousands of grass thatch houses on the West Bank of the Waimea River, but only one small cluster of houses on the East Bank, adjacent to where the fort is eventually built. Also, further up river on the east bank, Ellis draws a heiau with a large anuʻu tower in it. Artist John Weber wrote,

As we ranged down the coast from the East, in the ships, we had observed at every village one or more elevated white objects, like pyramids or rather obelisks; and one of these, which I guessed to be at least fifty feet high, was very conspicuous from the ships’ anchoring station, and seemed to be at no great distance up this valley. To have a nearer inspection of it, was the principal object of my walk. Our guide perfectly understood that we wished to be conducted to it. But it happened to be so placed, that we could not get at it, being separated from us by the pool of water [Waimea River]. However, there being another of the same kind within our reach, about a half a mile off, upon our side of the valley, we set out to visit that.

Kauaʻi is at this time was under the rule of chiefess Kamakahelei [mother of Kaumualiʻi] and her husband Kāneoneo.

“View of Atowa, One of the Sandwich Islands” Ellis, William Wade. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Presented by Captain A. W. F. Fuller through The Art Fund. 483 mm x 635 mm - graphite; ink; watercolour; pen. Link to original

December 1786 to March 1787

British traders Nathaniel Portlock and George Dixon in the King George and Queen Charlotte spend much of the winter in Waimea and establish very positive relationships with the community. Chiefess Kamakahelei has given birth to Kaumualiʻi, and her new husband Kaʻeokūlani is Kaumualiʻi’s father. Nathaniel Portlock notes that the chiefly residence of Kaʻeo is on the East Bank of the Waimea River near the shore (close to where the fort will be built). Ship supercargo William Beresford also provides a description of the East Bank in close proximity to the future location of the fort:

When I got on the banks of the river, one of the natives was paddling backwards and forwards in a small canoe, seemingly for his amusement; on this it occurred to me, that a cruise by water would be an agreeable variety, and perhaps give me an opportunity of seeing part of the country on the opposite shore, and more especially, as on the side of the hill directly facing me, there was a high wooden pile, seemingly of a quadrangular form, which I wished to examine. A couple of nails engaged my new waterman, and he took me with pleasure for a passenger…

I could not prevail on the man to land me near the place I have just been speaking of; he gave me to understand, that the pile I was desirous to see was a Morai, or place where they buried their dead, and that he durst not go near it.

March 1792

Captain George Vancouver invites Kaumualiʻi out to his vessel, Discovery, in Waimea Bay, and is impressed with Kaumualiʻi’s intelligence and maturity for a child of approximately 12 years of age:

His inquiries and observations, on this occasion, were not, as might have been expected from his age, directed to trivial matters; which either escaped his notice, or were by him deemed unworthy of it; but to such circumstances alone, as would have authorized questions from persons of matured years and some experience.

Kaumualiʻi had also taken the title of “King George,”… “not suffering his domestics to address him by any other name.”

February 1796

War breaks out between Kaumualiʻi and his half-brother, Keawe, following the death of Kaʻeo, and the battle is described by British trader Charles Bishop. Keawe’s army camped on the west side of the Waimea River, and Kaumualiʻi’s army camped on the east side. Charles Bishop wrote, “I am told it requires the utmost force of the Taboo to Prevent the armies rushing on to Death or Victory and which the contending chiefs politically exert…In this time, these intervals of war, they sit on the opposite banks of the stream conversing with each other as Friends.” Although Keawe was at first victorious, he was killed by a chief named Hikiki, and Kaumualiʻi then defeated Hikiki, gaining full control of Kauaʻi by 1797.

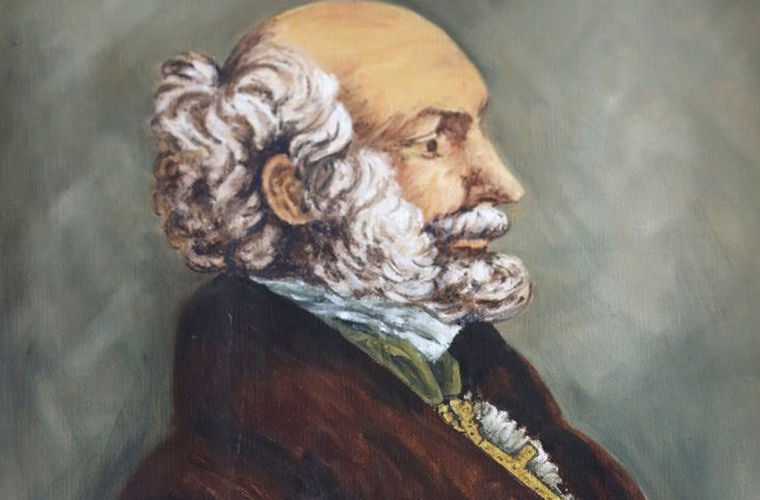

Kaumualiʻi

June 1804

Kauaʻi is under threat of invasion from Kamehameha I, which had first been avoided in 1796 when a storm destroyed Kamehameha’s invading fleet in Kaʻieʻie Waho Channel between Kauaʻi and Oʻahu. Russian Naval Captain Yuri Lisiansky on the Neva meets Kaumualiʻi on Kauaʻi and informs him that a plague has again decimated Kamehmeha’s invading force. Kaumualiʻi offers his kingdom to Russia if Lisiansky would be willing to use the Neva to protect Kauaʻi from Kamehameha I. Lisiansky declines the offer.

July(?) 1810

Kaumualiʻi sails to Oʻahu and meets with Kamehameha I. Kaumualiʻi agrees to pay tribute to Kamehameha and to bequeath rule of Kauaʻi to Kamehameha after his own death. In return, Kamehameha sends canoes filled with kapa made from all the different islands.

March 1813

During the War of 1812, Kaumualiʻi breaks his alliance with Kamehameha and enlists the assistance of American traders to protect Kauaʻi from Kamehameha.

February 8, 1814

Kaumualiʻi raises an American flag on a newly erected flagstaff in Waimea. This may be the same stone flagstaff foundation that is in the fort today.

April 3, 1814

Kaumualiʻi evicts 17 chiefs from Kauaʻi who have ties to Kamehameha and sends them back to Oʻahu on American vessels.

October 1814

As the War of 1812 is ending, all of Kaumaualiʻi’s American allies sail off for Canton, China with their trade goods, ships, and munitions.

January 31, 1815

A storm forces the Russian-American Company (RAC) trading vessel Bering (formerly the American trader Atahualpa) to run aground in front of Kaumualiʻi’s residential compound (kau hale) on the east bank of the Waimea River, stoving in the rudder case. Kaumualiʻi claims the salvage rights, and over 2,000 Hawaiians participated in the salvage efforts, which continued until March 1815.

December {?} 1815

Dr. George Anton Schäffer is sent from Sitka (New Archangel), Alaska to Hawaiʻi as a representative of the Russian-American Company to negotiate for the return of the Bering’s cargo and to establish favorable trade relationships. To avoid scrutiny from British and American competitors, Schäffer poses as a naturalist and arrives on Hawaiʻi Island aboard the American vessel Isabella with two other RAC employees in his company.

May 28, 1816

After attempting to befriend Kamehameha I and obtaining limited permission to establish a factory on land in Oʻahu, Schäffer arrives at Waimea Kauaʻi with approximately 60-80 Aleut hunters and native Russians who had arrived on the Otkrytie and Ilmen earlier in the month. More RAC employees arrive on the leaky vessel Kadʻiak at the end of June.

June 2, 1816

Schäffer achieved his original objectives and a great deal more. Kaumualii not only agreed to restore what remained of the Bering’s cargo, but in addition pledged allegiance to the Emperor Alexander I (Pierce 1976: 63). Schäffer and Kaumualiʻi sign a treaty that gives Kaumualiʻi protection from Kamehameha and a fully armed brig, which will be paid for in sandalwood. The RAC receives a sandalwood monopoly on Kauaʻi, the right to build factories and agricultural stations.

July 1, 1816

Kaumualiʻi and Schäffer sign a “secret treaty” giving Schäffer 500 armed native Hawaiians to reconquer other islands controlled by Kamehameha, and Schäffer agrees to provide munitions and additional ships to aid in the conquest. Kaumualiʻi agrees to supply labor to build a fort on each conquered island. Kaumualiʻi raises the Russian flag after gathering together traditional wooden god images and performing human sacrifice.

August 28, 1816

After sailing to Oʻahu to initiate arrangements to purchase two vessels, the Lydia and the Avon, from Americans, Schäffer sails to Hanalei on the north shore of Kauaʻi, and is enamored with the lush vegetation and agricultural potential.

September 12, 1816

Kaumualiʻi, enlisting Schäfferʻs skills as an engineer, has Schäffer lay out a plan for a fortress in Waimea as part of Kaumualiʻi’s own residential compound, which Schäffer names “Fort Elizabeth” (after the emperor’s wife). Kaumualiʻi puts his own people to work hauling stone to build the walls. Schäffer sends many RAC employees to Hanalei, which he renames “Schäfferthal” (Schäfferʻs Valley) where he begins construction of an earthwork fort that he names “Fort Alexander” (after Emperor Alexander I) in a location adjacent to the present Princeville Hotel. A smaller battery named Fort Barclay is built overlooking the mouth of the Hanalei River.

View of the fort (Elizabeth).

December 9, 1816

Schäffer had spent much of the last 3 months travelling between Hanalei, Waimea, and Hanapepe where RAC employees have spread out to plant newly introduced crops including cotton, grapes, and corn. On this day he visits the construction efforts of the fort in Waimea, where he notes that over 300 women, including Kaumauliʻi’s wives, are involved in the construction of the fort.

January 12, 1817

Kaumualiʻi and Schäffer both receive word from Alaska that the Governor of the RAC, Alexander Baranov, will not support the purchase of the American vessels that Schäffer had negotiated for on Oʻahu, which is the first indication that Schäffer would not be able to honor his part in the treaties.

February 6, 1817

Kaumualiʻi and Schäffer are again disappointed to learn that Lieutenant Otto Von Kotzebue, in command of the vessel Rurik, had sailed off from Hawaiʻi and Oaʻhu Islands without visiting Kauaʻi, and after meeting with Kamehameha, disavowing any Russian military support for Schäffer’s treaties on Kauaʻi.

May 7, 1817

American vessels arrive at Waimea with the rumor that the United States and Russia were at war and a group of American, British, and Kamehameha loyalists demand the expulsion of Schäffer and the RAC from Kauaʻi. Schäffer arrives from Hanapepe to meet Kaumualiʻi and about 1,000 of Kaumualiʻi’s warriors in Waimea, who forcibly expel Schäffer and other RAC men from Waimea. After stopping in Hanalei to recover some supplies, the RAC contingent sails for Honolulu, and Schäffer escapes the islands with his life on an American vessel on July 8, 1817. At no point does his journal refer

to any RAC employees being garrisoned in the fort in Waimea. The Waimea fort is noted to have had a magazine and flagstaff inside it before the Russians left, and the walls on the land side were not yet complete. Schäffer also claimed that timber from the Kad’iak had been used to help construct the fort, and another multi-story wooden RAC factory was built on other lands in Waimea. Kaumualiʻi raises a new blue and white flag at the fort divided into four triangular segments and each containing a sphere. In the coming years, Kaumualiʻi often refers to the fort as “my fort,” and not as “Fort Elizabeth” or the “Russian Fort.” The first recorded Hawaiian name for the fort, “Pāʻulaʻula,” appears in mid-nineteenth century Hawaiian land claims. It is unclear how early the Hawaiian name was in use.

March 1818

Kaumualiʻi again renews paying tribute to Kamehameha I by filling the hold of Kamehameha’s newly purchased vessel the Columbia with sandalwood, hogs, and vegetables. Peter Corney notes that an English flag was flying on “a very fine fort, mounting 30 guns” and containing “dungeons.” “The king, chiefs, and about 150 warriors live within it, and keep regular guard; they have a number of white men for the purpose of working the guns, etc.”

Fall 1818

A privateer named “Griffiths” is held captive inside the fort and executed outside the walls.

May 3, 1820

Kaumualiʻi’s son, Humehume, who had been raised in New England and fought as one of the first US marines in the War of 1812, returns to Waimea with the first Protestant missionaries to be stationed on Kauaʻi (the Whitneys and Ruggles). Kaumualiʻi fires a 21 gun salute from the fort. Kaumualiʻi and his Queen, Kapule, give the new arrivals houses adjacent to their own residential compound outside the fort, and on May 4, Kaumualiʻi formally gave control of the fort to Humehume and made him the district chief of Waimea. Samuel Ruggles notes that a celebrated heiau had once stood at the same spot.

Mercy Whitney described a 10-foot tall wall surrounding Kaumualiʻi’s residential compound that was different from the fort wall:

The fort is situated just above the mouth of the river, and the wall above mentioned between the fort and the sea. The beach from the mouth of the river runs out in a bow into the sea, so that the fort although near the mouth of the river stands some way back from the sand beach. The wall which enclosed our house, is built on the bow, in the form of a semi-circle the ends of the wall extending each way to the sea and leaving that side towards the sea entirely open. The ground on which the fort stands is a little elevated and the walls perhaps twice as high as the semi-circle.

Humehume

July 1821

King Kamehameha II (Liholiho) sails to Kauaʻi and takes Kaumualiʻi back to Oʻahu, where Kaumualiʻi marries Kaʻahumanu, a politically powerful widow of Kamehameha I. Humehume falls out of favor, and Kaumualiʻi’s sister, Maihinenui, becomes governor of Kauaʻi.

February 9, 1822

Humehume’s infant son is buried inside the fort. The missionary Mercy Whitney wrote, “a regular procession of two and two followed the corpse. Going into the fort in which the grave was dug seemed like entering a burying ground, more so than anything I have witnessed since I left America.”

August 8, 1824

Following the death of Kaumualiʻi on May 26, 1824, Kamehameha’s chiefs began taking more control of Kauaʻi. The chief Kahalaiʻa takes over control of the fort. Then Kaumualiʻi’s son Humehume led a rebellion that started with an attack on the fort at daybreak on August 8. The Hawaiian poet Niʻau, foreigners George Smith and Edward Tobridge, and several others were killed in the initial battle. At least some of those who died were buried inside the fort. This may be when the central platform that was probably the original adobe magazine with a “dungeon”/cellar was intentionally filled and turned into a burial platform. The 1824 battle culminated in the final unification of the Hawaiian Islands under the Kamehameha lineage. Chief Kalaiohi becomes the new commander of the fort, and is quickly replaced by Kukiku.

1830s

Kapuniai becomes the new commander of the fort, replacing Kukiku before Kaikioʻewa’s term as governor ends in 1839. It is in this era that the new lime plastered “Magazine and Armory” and “guardroom” (so labeled on an1885 map by George Jackson) were probably added to the interior. In April of 1834, Mercy Whitney noted that two men who had murdered a foreigner named “Giraud” were locked up inside the fort in irons. They were hung on gallows along with a man and woman who had been convicted of another murder on the north shore. By September 1839, the staffing of the fort appears to have been impermanent, at least as recorded by Louis Thiercelin, a French doctor who sailed into Waimea Bay at a time when the French were not on good terms with the monarchy:

In a fort, which overlooks the bay, they had collected a few cannons in rather poor condition and a hundred rusty rifles. The commandant called up the islanders to defend the fortress; however, as he did not have a permanent force, he had no means of gathering willing men among those who were matching our manouvre. Indeed, none of them was willing. Every man capable of holding a rifle preferred taking a walk in the mountains rather than keeping watch behind the walls of a dilapidated fort. So the commandant had no other option but to run after the deserters. The fort looked after itself.

1840s

Dozens of Land Commission Awards refer to soldiers (koa) who are stationed at the fort and claimed agricultural land (kula, loʻi) and house lots (pā hale) outside the fort. The name used to refer to the fort in Land Commission testimony is “Pāʻulaʻula.” By the 1840s, however, the era of major government investment in the fort seems to have ended, according to the description by Gorham Gilman in the summer of 1843:

It is an irregular wall of dirt, or adobies mounted by some twenty guns of every kind size and description, hardly any of them fit for discharging. The interior space is filled with houses, toombs etc. while a few decriped old men and women were its only guardians. Half a dozen Paihan shot thrown into it would completely demolish it.

1853

Fort Described by George Washington Bates:

Every gun was dismounted; the powder magazine was used as a native dwelling; while the interior of the old ruin was cultivated for the purpose of raising sweet potatoes. Some half dozen shoeless and stockingless—and almost ever thing else-less—soldiers, without arms and ammunition, were lounging over the useless guns, or stretched on their backs upon the hard stones, and under the tropical sun, with mouths wide open, and fast asleep. I knew not which looked the most desolate, the ruin itself, or its ruined defenders, yeleped soldiers.

1860

Up to 1860, there was still a Hawaiian commander appointed by the government who over saw a few soldiers, but the fort was entirely abandoned by this year (W.D. Alexander 1894).

September 1862

Fort Elizabeth or Pāʻulaʻula starts to be dismantled by Valdemar Knudsen, with usable rafters taken out of adobe structures, and WD Alexander notes that some dismantling continued until 1864. One account suggests that two of the largest cannon fell into the bay when the cannons were being hoisted aboard the ship that was being used to take the munitions away. Munitions included the following:

60 muskets with flint-locks

216 bayonets

16 swords no scabbards

20 [swords] without handles, rough

61 old cartridge boxes

6 heavy guns

12 18 lb. do [heavy guns]

26 4 and 6 Pounders

24 little guns.

1885

More than 20 years after the fort was dismantled, Hawaiian Government Surveyor George Jackson draws a fanciful map of the fort, not as it stood at the time, but as he imagined “it stood probably at the time the Doctor was its commandant.” Archaeological and archival investigations demonstrate that some of his interpretation, such as a “Trading House” outside the fort walls, was inaccurate. The supposed “Trading House” matches the location an material culture of an 1840s commandant named Paʻele, and the “barracks” appears to be the original magazine from 1817.

1890

First known photograph of the fort exterior, showing horses by the river, a person washing laundry and drying their pantaloons in a prickly-pear cactus, and a person sitting in the doorway of a thatched house on the ocean side of the fort.

1972

The State of Hawai‘i acquired the 17-acre property encompassing the fort structure to preserve the site and provide an opportunity for the public to visit and learn more about this period in Hawaiian history.

1972

The State of Hawai‘i acquired the 17-acre property encompassing the fort structure to preserve the site and provide an opportunity for the public to visit and learn more about this period in Hawaiian history.

October 1972

Three-week Archaeological Research of Fort Elizabeth by Patrick C. McCoy from Department of Anthropology Bernice P. Bishop Museum Honolulu, Hawaii.

1975

Archeological and Historical Research at Fort Elisabeth was made by Robert J Hommon, Catherine Stauder, David W. Cox and Francis K.W. Ching.

The archaeological and historical work required of the interpretation, stabilization, and restoration of Fort Elizabeth, required that a preliminary archaeological and historical investigation be made, along with test excavations to determine the limit of human occupation outside of the Fort.

1993-1994

Archeological Research by Peter R. Mills

November 11-13, 2017

In 2017, an open Fort Elizabeth forum was held, attended by representatives of a variety of parties concerned from members of local volunteer organizations and native people of the island to representatives of the academic community and government. One of the decisions of the forum was the holding of such global events on a regular basis, so that anyone could speak on the topic of preserving the Russian cultural heritage or offer their projects to preserve, study and popularize the Fort Elizabeth.